This article describes how to use ScalaMock in your tests. Because it is just an introduction to ScalaMock, it describes only the basic usage of this mocking framework. For more details, please refer to the User Guide.

ScalaMock 7

This is a quickstart using scalamock 7. If you want plain old scalamock, please refer to ScalaMock section.

I will use sbt and scalatest, just because I’m more familiar with them. If you are using something else, please refer to the Installation and Integration sections.

API is located in org.scalamock.stubs package in Stubs trait.

What you can do with it:

- Stubbing interface using

stubmethod, for typeTit returnsStub[T] - Setting up expected method result based on arguments using

returnsmethod on selected method fromStub[T] - Getting number of times method was invoked using

timesmethod on selected method fromStub[T] - Getting method arguments with which it was invoked using

callsmethod on selected method fromStub[T]. It returns a list, where each item is one call. - Verifying order using

given CallLog,isBeforeandisAftermethods on selected method fromStub[T]

If you are not understanding what am I talking about - please proceed to the next sections with very basic examples.

Installation

libraryDependencies += "org.scalamock" %% "scalamock" % "7.1.0" % Test

libraryDependencies += "org.scalatest" %% "scalatest" % "3.2.19" % Test

Test / scalacOptions := "-experimental"

Really quick and easy example

This example shows basic features of ScalaMock to get you started.

Let’s assume we have a Greetings functionality that we want to test.

For simplicity’s sake, it has only one method called sayHello which can format a name and prints a greeting.

object Greetings:

trait Formatter:

def format(s: String): String

object EnglishFormatter extends Formatter:

def format(s: String): String = s"Hello $s"

object GermanFormatter extends Formatter:

def format(s: String): String = s"Hallo $s"

object JapaneseFormatter extends Formatter:

def format(s: String): String = s"こんにちは $s"

def sayHello(name: String, formatter: Formatter): Unit =

println(formatter.format(name))

With ScalaMock, we can test the interactions between this method and a given Formatter.

To be able to mock things, you need to mix-in the org.scalamock.stubs.Stubs into your test class.

For example, we can check that the name is actually used in the call to our formatter, and that it is called once (and only once):

import org.scalatest.funsuite.AnyFunSuite

import org.scalatest.matchers.should.Matchers

import org.scalamock.stubs.Stubs

class ReallySimpleExampleTest extends AnyFunSuite, Matchers, Stubs:

test("sayHello"):

val formatterStub = stub[Formatter]

formatterStub.format.returns(_ => "Ah, Mr Bond. I've been expecting you")

Greetings.sayHello("Mr Bond", formatterStub)

formatterStub.format.times shouldBe 1 // method called exactly once

formatterStub.format.calls shouldBe List("Mr Bond") // check that name is Mr Bond, this list has one item per each method invokation

Also you can set up result depending on method arguments.

val formatterStub = stub[Formatter]

formatterStub.format.returns(name => s"Ah, $name. I've been expecting you")

Greetings.sayHello("Mr Grinch", formatterStub)

formatterStub.format.times shouldBe 1 // method called exactly once

formatterStub.format.calls shouldBe List("Mr Grinch") // name is Mr Grinch

Leaderboad example

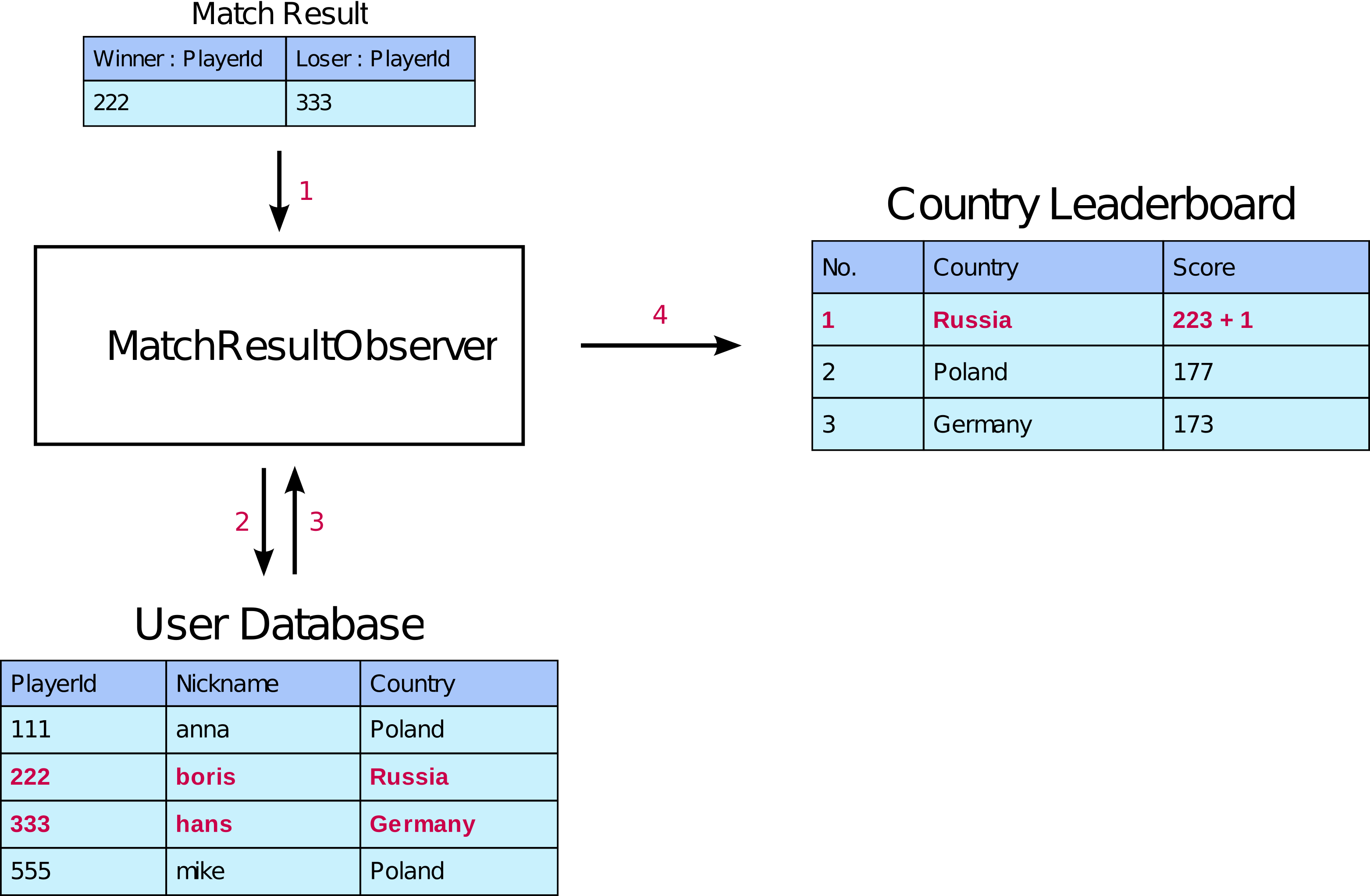

This example assumes that we’re writing code that is responsible for updating a Country Leaderboard (i.e. Top Countries) every time a match between two players finishes in an online multiplayer game.

They say that picture is worth a thousand words, so before we get into details let’s look at a diagram:

The Player class represents a player and MatchResult describes the result of a played game between two players. Each player has its unique id and country it came from:

type PlayerId = Int

case class Player(id: PlayerId, nickname: String, country: Country)

case class MatchResult(winner: PlayerId, loser: PlayerId)

There is also the CountryLeaderboard trait that describes the Country Leaderboard interface:

case class CountryLeaderboardEntry(country: Country, points: Int)

trait CountryLeaderboard:

def addVictoryForCountry(country: Country): Unit

def getTopCountries(): List[CountryLeaderboardEntry]

The class we are going to test is called MatchResultObserver since its responsibility is to observe created MatchResult instances:

class MatchResultObserver(playerDatabase: PlayerDatabase, countryLeaderBoard: CountryLeaderboard):

def recordMatchResult(result: MatchResult): Unit =

val player = playerDatabase.getPlayerById(result.winner)

countryLeaderBoard.addVictoryForCountry(player.country)

Finally, there is the PlayerDatabase trait that provides an abstract interface for accessing player information from some database:

trait PlayerDatabase:

def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId): Player

As mentioned before, the MatchResultObserver is the class we are going to test. We assume that all classes that implement PlayerDatabase and CountryLeaderboard traits are tested in different test suites.

Objects interacting with a tested class

MatchResultObserver is a very simple class and it should be easy to test it. Unfortunately, the only available implementation of PlayerDatabase is one that uses a relational database to store and retrieve players:

class RealPlayerDatabase(

dbConnectionPool: DbConnectionPool,

databaseConfig: DatabaseConfig,

securityManager: SecurityManager,

transactionManager: TransactionManager) extends PlayerDatabase:

override def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId) = ???

It would be a nightmare to setup a database, fill it with sample players, create all of RealPlayerDatabase’s dependencies (like TransactionManager) and the dependencies of those dependencies.

Fortunately, mocking is useful in this kind of situation because instead of testing MatchResultObserver with RealPlayerDatabase we can test it with a much simpler PlayerDatabase implementation. We could directly implement PlayerDatabase, for example:

class FakePlayerDatabase extends PlayerDatabase:

override def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId) : Player =

if playerId == 222 then Player(222, "boris", Countries.Russia)

else if playerId == 333 then Player(333, "hans", Countries.Germany)

else ???

In this case it does not look that bad. But implementing complex traits or having a fake implementation generic enough to handle all test cases can be a really cumbersome and error-prone task.

This is where ScalaMock comes into play.

Stubbing objects interacting with a tested class

With ScalaMock you can create objects that pretend to implement some trait or interface. Then you can instruct that “faked” object how it should respond to all interactions with it. For example:

// create fakeDb stub that implements PlayerDatabase trait

val fakeDb = stub[PlayerDatabase]

// configure fakeDb behavior

fakeDb.getPlayerById.returns:

case 222 => Player(222, "boris", Countries.Russia)

case 333 => Player(333, "hans", Countries.Germany)

case other => Player(other, "Walt", Countries.USA)

// use fakeDb

assert(fakeDb.getPlayerById(222).nickname == "boris")

Testing with ScalaMock

To provide mocking support in ScalaTest suites just mix your suite with org.scalamock.stubs.Stubs.

import org.scalamock.stubs.Stubs

import org.scalatest.FlatSpec

class MatchResultObserverTest extends FlatSpec, Stubs:

val winner = Player(id = 222, nickname = "boris", country = Countries.Russia)

val loser = Player(id = 333, nickname = "hans", country = Countries.Germany)

"MatchResultObserver" should "update CountryLeaderBoard after finished match" in {

// create a call log

given CallLog = CallLog()

val countryLeaderBoardStub = stub[CountryLeaderboard]

val userDetailsServiceStub = stub[PlayerDatabase]

// configure stubs

countryLeaderBoardStub.addVictoryForCountry.returns(_ => ())

userDetailsServiceStub.getPlayerById.returns:

case loser.id => loser

case winner.id => winner

// run system under test

val matchResultObserver = new MatchResultObserver(userDetailsServiceStub, countryLeaderBoardStub)

matchResultObserver.recordMatchResult(MatchResult(winner = winner.id, loser = loser.id))

// verify

assert(countryLeaderBoardStub.addVictoryForCountry.calls == List(Countries.Russia))

assert(userDetailsServiceStub.getPlayerById.calls == List(winner.id))

// verify order of calls using CallLog

assert(userDetailsServiceStub.getPlayerById.isBefore(countryLeaderBoardStub.addVictoryForCountry))

}

ScalaMock

Installation

To use ScalaMock in sbt with ScalaTest add the following to your build.sbt. ScalaMock also supports Specs2 as a testing framework.

Alternative experimental API from scalamock 7 supports any testing framework, but I will use

libraryDependencies += "org.scalamock" %% "scalamock" % "7.1.0" % Test

libraryDependencies += "org.scalatest" %% "scalatest" % "3.2.19" % Test

If you don’t use sbt or ScalaTest please check the Installation chapter in the User Guide for more information.

Really quick and easy example

The full code for this really quick example is on Github and shows a few of the basic features of ScalaMock to get you started.

Let’s assume we have a Greetings functionality that we want to test.

For simplicity’s sake, this has only one method called sayHello which can format a name and prints a greeting.

object Greetings {

trait Formatter { def format(s: String): String }

object EnglishFormatter extends Formatter { def format(s: String): String = s"Hello $s" }

object GermanFormatter extends Formatter { def format(s: String): String = s"Hallo $s" }

object JapaneseFormatter extends Formatter { def format(s: String): String = s"こんにちは $s" }

def sayHello(name: String, formatter: Formatter): Unit = {

println(formatter.format(name))

}

}

With ScalaMock, we can test the interactions between this method and a given Formatter.

To be able to mock things, you need to mix-in the org.scalamock.scalatest.MockFactory into your test class.

For example, we can check that the name is actually used in the call to our formatter, and that it is called once (and only once):

import org.scalamock.scalatest.MockFactory

import org.scalatest.funsuite.AnyFunSuite

class ReallySimpleExampleTest extends AnyFunSuite with MockFactory {

test("sayHello") {

val mockFormatter = mock[Formatter]

mockFormatter.format.expects("Mr Bond").returning("Ah, Mr Bond. I've been expecting you").once()

Greetings.sayHello("Mr Bond", mockFormatter)

}

}

For all other examples, we did omit the text names and just show the relevant calls to the ScalaMock API.

If you are used to Mockito, ScalaMock can defer verifications for you too. Just use a stub instead:

val mockFormatter = stub[Formatter]

val bond = "Mr Bond"

mockFormatter.format.when(bond).returns("Ah, Mr Bond. I've been expecting you")

Greetings.sayHello(bond, mockFormatter)

mockFormatter.format.verify(bond).once()

Some other features:

- throwing an exception in a mock

val brokenFormatter = mock[Formatter]

brokenFormatter.format.expects(*).throwing(new NullPointerException).anyNumberOfTimes()

intercept[NullPointerException] {

Greetings.sayHello("Erza", brokenFormatter)

}

- dynamically responding to a parameter with

onCall

val australianFormat = mock[Formatter]

australianFormat.format.expects(*).onCall { s: String => s"G'day $s" }.twice()

Greetings.sayHello("Wendy", australianFormat)

Greetings.sayHello("Gray", australianFormat)

- verifying parameters dynamically (two flavours)

val teamNatsu = Set("Natsu", "Lucy", "Happy", "Erza", "Gray", "Wendy", "Carla")

val formatter = mock[Formatter]

def assertTeamNatsu(s: String): Unit = {

assert(teamNatsu.contains(s))

}

// argAssert fails early

formatter.format.expects(argAssert(assertTeamNatsu _)).onCall { s: String => s"Yo $s" }.once()

// 'where' verifies at the end of the test

formatter.format.expects(where { s: String => teamNatsu contains(s) }).onCall { s: String => s"Yo $s" }.twice()

Greetings.sayHello("Carla", formatter)

Greetings.sayHello("Happy", formatter)

Greetings.sayHello("Lucy", formatter)

- call ordering

Here we just use inAnyOrder, but inSequence is available too. These two imperatives can also be nested to make the order of calls really expressive!

val mockFormatter = mock[Formatter]

inAnyOrder {

mockFormatter.format.expects("Mr Bond").returns("Ah, Mr Bond. I've been expecting you")

mockFormatter.format.expects("Natsu").returns("Not now Natsu!").atLeastTwice()

}

Greetings.sayHello("Natsu", mockFormatter)

Greetings.sayHello("Natsu", mockFormatter)

Greetings.sayHello("Mr Bond", mockFormatter)

Greetings.sayHello("Natsu", mockFormatter)

Leaderboad example

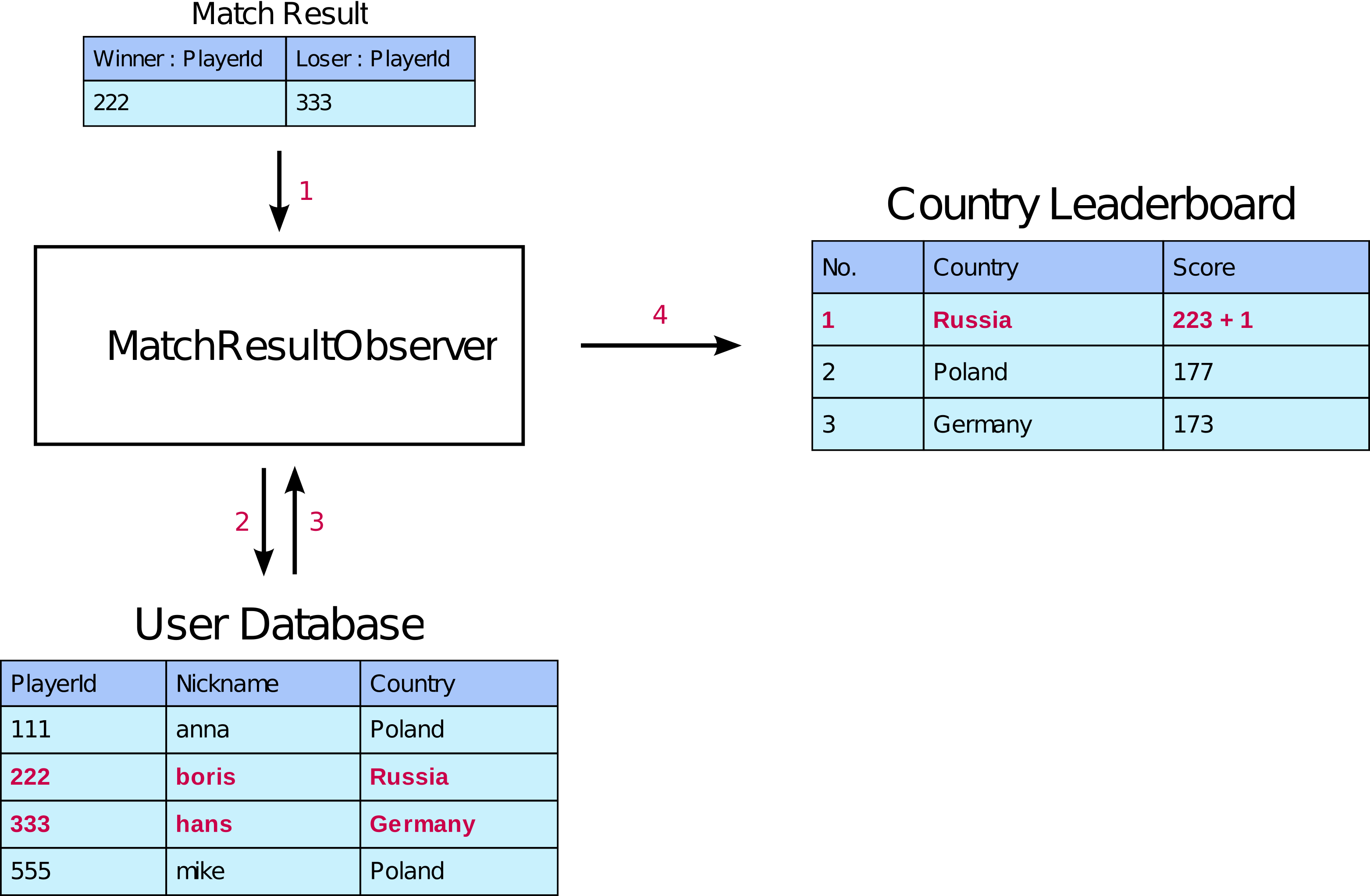

This example assumes that we’re writing code that is responsible for updating a Country Leaderboard (i.e. Top Countries) every time a match between two players finishes in an online multiplayer game.

They say that picture is worth a thousand words, so before we get into details let’s look at a diagram:

The Player class represents a player and MatchResult describes the result of a played game between two players. Each player has its unique id and country it came from:

type PlayerId = Int

case class Player(id: PlayerId, nickname: String, country: Country)

case class MatchResult(winner: PlayerId, loser: PlayerId)

There is also the CountryLeaderboard trait that describes the Country Leaderboard interface:

case class CountryLeaderboardEntry(country: Country, points: Int)

trait CountryLeaderboard {

def addVictoryForCountry(country: Country): Unit

def getTopCountries(): List[CountryLeaderboardEntry]

}

The class we are going to test is called MatchResultObserver since its responsibility is to observe created MatchResult instances:

class MatchResultObserver(playerDatabase: PlayerDatabase, countryLeaderBoard: CountryLeaderboard) {

def recordMatchResult(result: MatchResult): Unit = {

val player = playerDatabase.getPlayerById(result.winner)

countryLeaderBoard.addVictoryForCountry(player.country)

}

}

Finally, there is the PlayerDatabase trait that provides an abstract interface for accessing player information from some database:

trait PlayerDatabase {

def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId): Player

}

As mentioned before, the MatchResultObserver is the class we are going to test. We assume that all classes that implement PlayerDatabase and CountryLeaderboard traits are tested in different test suites.

Objects interacting with a tested class

MatchResultObserver is a very simple class and it should be easy to test it. Unfortunately, the only available implementation of PlayerDatabase is one that uses a relational database to store and retrieve players:

class RealPlayerDatabase(

dbConnectionPool: DbConnectionPool,

databaseConfig: DatabaseConfig,

securityManager: SecurityManager,

transactionManager: TransactionManager) extends PlayerDatabase {

override def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId) = ???

}

It would be a nightmare to setup a database, fill it with sample players, create all of RealPlayerDatabase’s dependencies (like TransactionManager) and the dependencies of those dependencies.

Fortunately, mocking is useful in this kind of situation because instead of testing MatchResultObserver with RealPlayerDatabase we can test it with a much simpler PlayerDatabase implementation. We could directly implement PlayerDatabase, for example:

class FakePlayerDatabase extends PlayerDatabase {

override def getPlayerById(playerId: PlayerId) : Player = {

if (playerId == 222) Player(222, "boris", Countries.Russia)

else if (playerId == 333) Player(333, "hans", Countries.Germany)

else ???

}

}

In this case it does not look that bad. But implementing complex traits or having a fake implementation generic enough to handle all test cases can be a really cumbersome and error-prone task.

This is where ScalaMock comes into play.

Stubbing objects interacting with a tested class

With ScalaMock you can create objects that pretend to implement some trait or interface. Then you can instruct that “faked” object how it should respond to all interactions with it. For example:

// create fakeDb stub that implements PlayerDatabase trait

val fakeDb = stub[PlayerDatabase]

// configure fakeDb behavior

fakeDb.getPlayerById.when(222).returns(Player(222, "boris", Countries.Russia))

fakeDb.getPlayerById.when(333).returns(Player(333, "hans", Countries.Germany))

// use fakeDb

assert(fakeDb.getPlayerById(222).nickname == "boris")

Mocking objects interacting with a tested class

ScalaMock supports two mocking styles: Expectations-First Style (mocks) and Record-then-Verify (stubs).

Previously we used a stub to create a fake PlayerDatabase and now we will use a mock CountryLeaderboard to set our test expectations:

// create CountryLeaderboard mock

val countryLeaderBoardMock = mock[CountryLeaderboard]

// set expectations

countryLeaderBoardMock.addVictoryForCountry.expects(Countries.Germany).returns(())

// use countryLeaderBoardMock

countryLeaderBoardMock.addVictoryForCountry(Countries.Germany) // OK

countryLeaderBoardMock.addVictoryForCountry(Countries.Russia) // throws TestFailedException

To read more about the differences between mocks and stubs, please see the chapter Choosing your mocking style in the User Guide.

Testing with ScalaMock

To provide mocking support in ScalaTest suites just mix your suite with org.scalamock.scalatest.MockFactory.

Note: You must use AsyncMockFactory instead of regular MockFactory with ScalaTest async specs - more on how to do that is in the User Guide.

import org.scalamock.scalatest.MockFactory

import org.scalatest.FlatSpec

class MatchResultObserverTest extends FlatSpec with MockFactory {

val winner = Player(id = 222, nickname = "boris", country = Countries.Russia)

val loser = Player(id = 333, nickname = "hans", country = Countries.Germany)

"MatchResultObserver" should "update CountryLeaderBoard after finished match" in {

val countryLeaderBoardMock = mock[CountryLeaderboard]

val userDetailsServiceStub = stub[PlayerDatabase]

// set expectations

countryLeaderBoardMock.addVictoryForCountry.expects(Countries.Russia).returns(())

// configure stubs

userDetailsServiceStub.getPlayerById.when(loser.id).returns(loser)

userDetailsServiceStub.getPlayerById.when(winner.id).returns(winner)

// run system under test

val matchResultObserver = new MatchResultObserver(userDetailsServiceStub, countryLeaderBoardMock)

matchResultObserver.recordMatchResult(MatchResult(winner = winner.id, loser = loser.id))

}

}

To use ScalaMock with different testing frameworks please check the Integration with testing frameworks chapter in the User Guide.

Further reading

ScalaMock has many powerful features. The example below shows some of them:

val httpClient = mock[HttpClient]

val counterMock = mock[Counter]

inAnyOrder {

httpClient.sendRequest.expects(Method.GET, *, *).returns(()).twice

httpClient.sendRequest.expects(Method.POST, "http://scalamock.org", *).returns(()).noMoreThanOnce

httpClient.sendRequest.expects(Method.POST, "http://example.com", *).returning(Http.NotFound)

inSequence {

counterMock.increment.expects(*).onCall { arg: Int => arg + 1}

counterMock.decrement.expects(*).onCall { throw new RuntimeException() }

}

}

Please read the User Guide for more details.